While I’ve come across advice in the writing world that pushes reluctant writers to eventually take the plunge and try submitting their work, it is far outweighed by that desperately trying to instill some sort of reality check.

I have never been one to expect I will “get good” at writing within a few months and so the reality checks I keep coming across have always made me think, “well, duh!” What I do know about myself with cast iron certainty is that I have potential that can be developed and I firmly believe that to be successful at something requires an initial seed of talent or aptitude.

But how long is it going to take to germinate that seed? What is a realistic time scale?

Many writing advice books and websites quote the figure of 10 years; it takes 10 years to hone your writing craft to the point of proficiency. Perhaps this figure is just used as a scaremongering tactic to discourage those who think writing is a quick and easy way to make money, but maybe not.

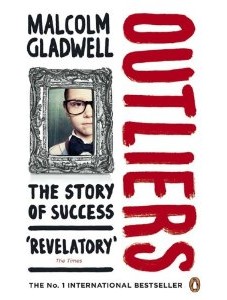

Published in 2008, the book “Outliers: The Story of Success” by Malcolm Gladwell generated (or at least made popular) the idea of the 10,000 hour rule; to become successful at something requires a cumulative 10,000 hours of practice and development.

Published in 2008, the book “Outliers: The Story of Success” by Malcolm Gladwell generated (or at least made popular) the idea of the 10,000 hour rule; to become successful at something requires a cumulative 10,000 hours of practice and development.

If you could devote an average of three hours a day to writing, in ten years you would pretty much hit the 10,000 hour mark. Many writers juggle full time work with their writing, especially in the early phases of their development, so perhaps there is something to both of these numbers.

Some people might see such figures as daunting, but I see it as a rite of passage, or an apprenticeship.

In the two years I’ve been writing seriously, I’ve learned a huge amount; improved my technique, gained better understanding of many aspects and discovered a lot about my own strengths and weaknesses. I’ve dipped a toe in the waters of publishing and met loads of fellow writers. But I don’t kid myself that I’m even half way there yet. I’m prepared for the long haul. What about you?